5 - ntfsm

Time spent: ~2 hour

Tools used: Ghidra

Challenge 5 is where we finally start reversing real binaries for this year. You are presented with an executable file that stores roughly 16MB, that asks for a password:

This is a really great mid-tier difficulty challenge, perhaps one of my favorites. Let’s dive in.

Orientation

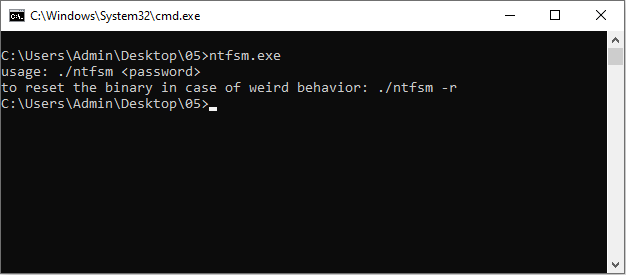

Running the binary without any parameters reveals two things.

Firstly, the program expects a password as the first commandline argument.

Secondly, there seems to be some interesting extra flag -r seemingly to reset the challenge “in case of weird behavior”:

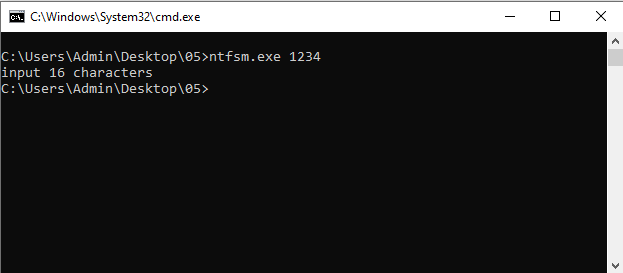

Typing in a password reveals that this password needs to be 16 characters long.

Typing 16 characters makes the program spasm out, show a bunch of new terminal windows to open and close, as well as pop up many message boxes with the text "Hello there, Hacker!", before finally printing the text wrong!.

If you know anything about NTFS, the challenge name kind of implies already what may be going on.

NTFS has some interesting features, including Alternate Data Streams.

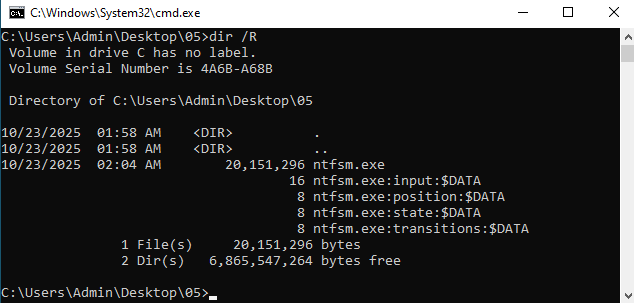

And indeed, after running the binary once with a 16 character password, you can run dir /R to reveal that 4 other data streams are created next to the binary:

The names of these alternate data streams seem to indicate this is some kind of state machine. But without knowing what this state machine looks like, we probably won’t get much further than this.

Time to open Ghidra.

Finding the State Machine

Given the pre-work that we just did, we have a fairly good sense of what to look for.

We want to find references to the names of the alternate data streams (i.e., "input", "position", "state" and "transitions"), as well as some APIs that write to files.

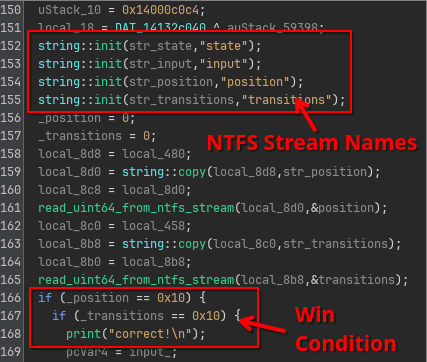

This turns out to be very straight forward, as these strings are immediately used in the main function of the program (14000c0b0):

In this code, we can immediately identify based on the read function calls that the position and transitions data streams are merely containing a single uint64.

Furthermore, based on the if statements that follow, the win condition for this challenge is to make the values of both the position and transitions streams 16 (0x10).

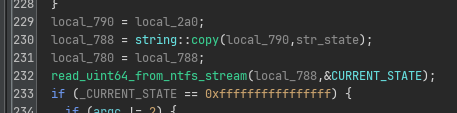

A little further down we also see that state is also just an uint64:

And as expected, this state variable is used to index into an STATES array (140c687b8) to handle the current state.

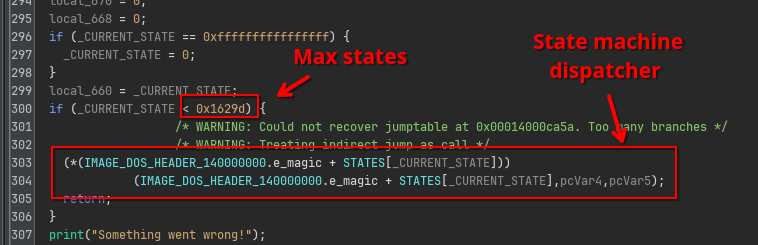

This state array is a bunch of RVAs that all point to the function implementing the code handling the current state:

But there are 90781 states, way too many to explore on our own. How do we navigate this?

Reversing a Single State

When the number of states is this large, my initial intuition is always that this is not something we want to do manually. However, more importantly, it is also very likely that the challenge author also did not make this many states manually either. In other words, there must be a pattern that we can recognize and use to our advantage. Therefore, let’s just explore the first state and see if there are any similarities with other states.

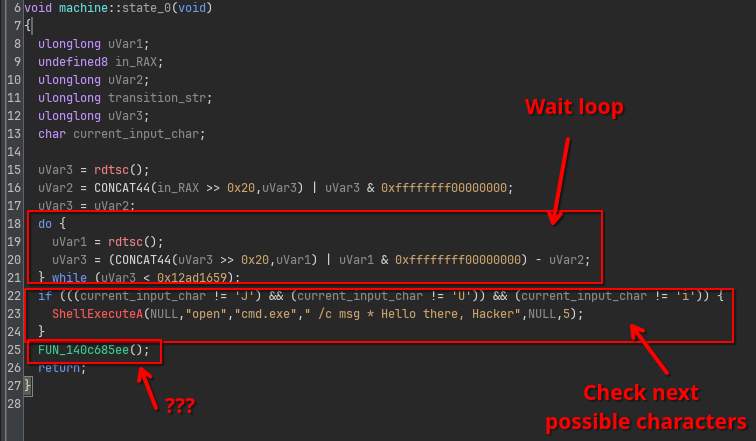

If we look at state 0 (RVA 0x860241 and thus FUN_140860241), we see that the decompiler has a bit of trouble understanding exactly what is going on.

First, we see the state starts with a waiting loop that spins for some time.

Then, the state checks the current character for some options (in this case J, U or i).

Finally, it ends with a function call… except this is not really a function call.

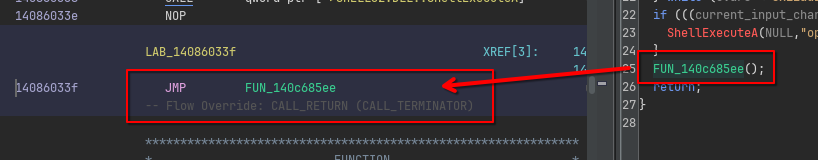

If we look in the listing, we actually see this is a JMP instruction treated as a CALL by Ghidra’s analyzer:

This happens sometimes when the control flow is “unusual enough” to Ghidra that it cannot resolve it to normal control flow structures like if statements, switches or loops.

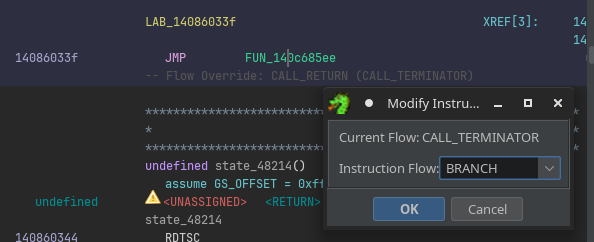

Nothing to worry about though, we can adjust this by forcing Ghidra to treat this JMP as a branch, by right clicking on the instruction, and using Modify Instruction Flow... to force it as a BRANCH instead:

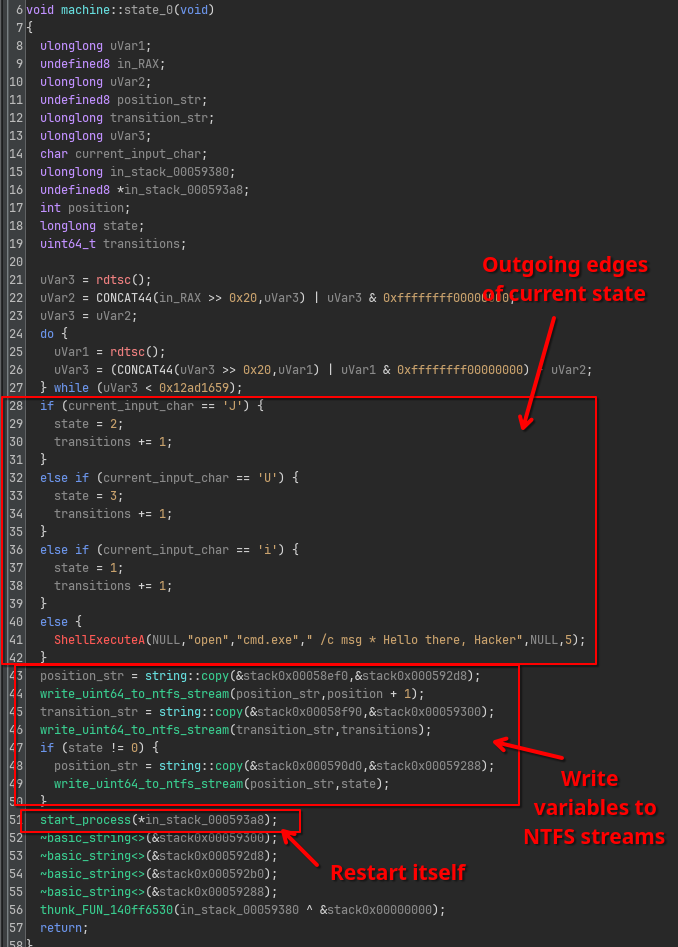

Now the code looks much cleaner:

This code reveals some very important facts.

First, we see that the outgoing edges for this state 0 are now very clearly defined:

Jpoints to state2Upoints to state3ipoints to state1.- Anything else will result in a message

"Hello there, Hacker"as we’ve seen before in our initial orientation step, and we remain in state0.

The second important fact here is that transitions variable is only updated when one of the outgoing edges is actually taken.

Recall from earlier that we needed both position and transitions to be equal to 10.

This implies we should never hit the else block of this long if chain.

Finally, after writing all the new values of position, state and transitions the program restarts itself, effectively executing the next state

This means that, to get to our good boy message, we need to type in a password of 16 characters that result in exactly 16 valid transitions to be made in the state machine.

Exploring the State Space

This challenge now has turned into a classic search problem that you can find in any CompSci algorithms course. We need to parse the entire state machine, extract all the edges implied by the code in each state handler function, and use a search algorithm like Breath-First-Search to find all paths that are exactly 16 characters long. We can all do this in a Ghidra script.

First, we need to extract the entry points of all state handler functions in the binary. This is easy, because they are hardcoded in the huge array:

final var ADDRESS_STATES = currentProgram

.getAddressFactory()

.getAddress("0x140c687b8");

var memory = currentProgram.getMemory();

var rvas = new int[90781];

memory.getInts(ADDRESS_STATES, rvas);

Second, we need to draw the edges between the states. This means that for each state function, we need to extract the outgoing edges. The key point here is to recognize that all relevant code for this looks more or less the same. For example, the if statements look like the following:

CMP byte ptr [RSP + 0x3bb8c], 0x4a // 'J'

JZ LAB_1408602ce

CMP byte ptr [RSP + 0x3bb8c], 0x55 // 'U'

JZ LAB_1408602ef

CMP byte ptr [RSP + 0x3bb8c], 0x69 // 'i'

JZ LAB_1408602ad

JMP LAB_140860310

Additionally, inside each referenced block, we should be seeing code that sets the state variable:

MOV qword ptr [RSP + 0x58d30], <next state>

We can then start at state 0, find these instruction patterns and extract the outgoing edges, and add the newly discovered states to our stack until we discover no more new states.

private HashMap<Integer, Map<Byte, Integer>> buildGraph(int[] rvas, FunctionManager manager) throws Exception {

var machine = new HashMap<Integer, Map<Byte, Integer>>(); // state -> (byte -> state)

var agenda = new Stack<Integer>();

// Start exploring at state 0

agenda.push(0);

println("Parsing machine...");

while (!agenda.isEmpty() && !monitor.isCancelled()) {

int state = agenda.pop();

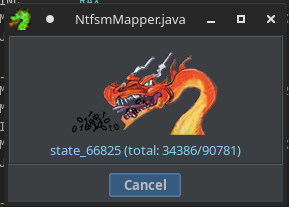

monitor.setMessage("state_%d (total: %d/%d)".formatted(state, machine.size(), rvas.length));

var address = currentProgram.getImageBase().add(rvas[state]);

// Make sure there is a function at the address.

var function = manager.getFunctionAt(address);

if (function == null) {

disassemble(address);

createFunction(address, "state_%d".formatted(state));

}

// Parse the states (with pattern matching)

var nextStates = parseNextStates(address);

machine.put(state, nextStates);

// Schedule the newly discovered states for processing.

for (var entry : nextStates.entrySet()) {

if (!machine.containsKey(entry.getValue()) && !agenda.contains(entry.getValue())) {

agenda.push(entry.getValue());

}

}

}

}

private Map<Byte, Integer> parseNextStates(Address address) throws Exception {

var result = new HashMap<Byte, Integer>();

int max = 0; // sanity check.

var listing = currentProgram.getListing();

var iterator = listing.getInstructions(address, true);

while (max < 100 && iterator.hasNext()) {

max++;

// Get next instruction.

var instruction = iterator.next();

var formatted = instruction.toString();

// Check if we reached the end of the if statements.

if (formatted.startsWith("JMP")) {

break;

}

// Check if we are at the next CMP+JZ instruction sequence.

if (formatted.startsWith("CMP byte ptr [RSP + ")) {

// Extract comparator (excuse my ugly parsing code :-))

byte value = Byte.parseByte(formatted.split(",0x")[1], 16);

formatted = iterator.next().toString();

if (formatted.startsWith("JZ")) {

// Extract branch target.

var target = currentProgram.getAddressFactory().getAddress(formatted.split(" ")[1]);

// Find the assignment of the next state variable behind the jump target.

formatted = listing.getInstructionAt(target).toString();

if (formatted.startsWith("MOV qword ptr [RSP + ")) {

var nextState = Integer.parseInt(formatted.split(",0x")[1], 16);

result.put(value, nextState);

}

}

}

}

return result;

}

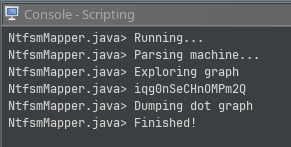

This takes a couple seconds to run:

Once we have all the edges drawn, we can simply explore it up to a depth of 16:

class State {

public int state;

public String path;

public State(int state, String path) {

this.state = state;

this.path = path;

}

}

// Build the entire state machine graph.

var machine = buildGraph(rvas, manager);

// Explore using BFS

var agenda = new ArrayDeque<State>();

agenda.add(new State(0, ""));

println("Exploring graph");

while (!agenda.isEmpty()) {

var current = agenda.remove();

// Are we at the desired length? Print the current path.

if (current.path.length() == 16) {

println(current.path);

continue;

}

// If not, keep looking.

var transitions = machine.get(current.state);

for (var transition : transitions.entrySet()) {

byte c = transition.getKey();

int target = transition.getValue();

agenda.add(new State(target, current.path + (char) c));

}

}

It so turns out this has exactly one solution:

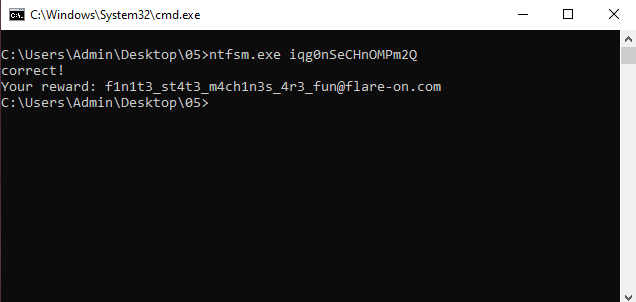

Plugging this in the original program reveals the flag: